|

From the earliest days of planning the Mekong First Descent it became apparent that the greatest physical and political obstacles to completing the expedition successfully would lay within the confines of Kham Tibet.

Unlike Lhasa and various other prefectures of the Tibetan Autonomous Region (TAR) the Kham remains heavily restricted to foreigners. This closed area status was earned largely due to the fierce resistance communist forces faced from the local inhabitants, which lasted long into the 1960's with American support.

External support of anti communist militants in the Kham has left a legacy of considerable distrust towards foreigners among members of the "Party" who now rule over this still wild region. Gaining permission to travel for weeks, without being constantly tailed by a government "watcher' was in itself a considerable task, yet this was not the main problem.

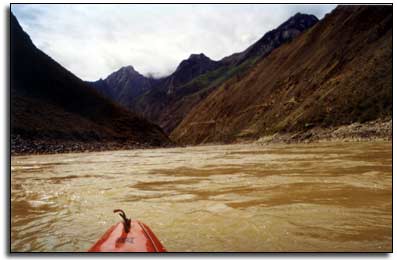

Over hundreds of millions of years the Mekong River has carved out one of the most extreme and desolate environments to be found on earth within the Kham in the form of the Mekong Gorges. In its infancy the river meanders gracefully through the high plains and mountain fringed valleys of Qinghai Province, picking up volume with little turbulence before reaching its adolescence just north of the Kham Capital of Chamdo. The increasingly powerful river runs off the rails at this point undertaking a violent descent off the Tibetan plateau that continues for many hundreds of kilometers. Some of the world's deepest and least accessible gorges have been carved out of the Himalaya by the relentless action of the water and

even the rugged and resourceful Tibetans who eek an existence from the most testing of environments have not managed to inhabit long sections of the river housed in ravines up to 1600 meters deep.

even the rugged and resourceful Tibetans who eek an existence from the most testing of environments have not managed to inhabit long sections of the river housed in ravines up to 1600 meters deep.

As far as my research could reveal, only two river expeditions have ever been attempted along the Kham section of the Mekong. The first, a Japanese team in 1998, was violently attacked and robbed by bandits only hours after crossing the border into the TAR. Nevertheless they succeeded in navigating the relatively mild section of river from Qinghai to Chamdo.

The second took place only weeks before my own attempt and planned a full navigation from Chamdo to the Yunnan border. This attempt led by Pete Winn of Shangrila River Expeditions was made up of an experienced international team most of whom had previous exploratory experience on remote sections of the Mekong. Starting at Chamdo they rafted and kayaked just 80 miles of the planned 400 mile stretch before calling the expedition off. Slow progress down increasingly treacherous sections of rapids compounded by extreme weather conditions and heavily laden rafts led to them making a tough decision. Knowing that they were about to enter an extremely remote and much steeper section where trekking out would be almost impossible and in the knowledge that with their current rate of progress the team would quite possibly run out of food supplies before exiting the gorges, they wisely chose to trek out. A decision I would find out later quite probably saved lives. Even from a relatively accessible section of the gorges where farmer's homesteads, trails and packhorses were accessible the trek out to a road took a week to complete.

This left the most challenging and remote section of the entire Mekong River unchallenged and I was thoroughly looking forward to having a go at it. Finally, delays caused by permit problems and sponsors not coming forth with pledged funds had placed my departure at the changing of the seasons and the start of the summer rains. This was far from ideal; if the river were to go into flood while I was in the gorges I would be left with no way out. This factor gave my departure an extreme sense of urgency and my strategy was simple, get through the gorges as fast as humanly possible before the heavy rains hit and turned the canyons into a kayaker's hell.

I had to make room for food, lots of food. Fitting 14 days worth of food supplies and camping gear in a boat just 2 and a half meters long is no easy feat. A plastic sheet and space blanket replaced my north face tent. I only packed one liter of water and would refill at the numerous crystal clear cascades that

plummeted into the mainstream and my first aid kit, clothes and other accessories were halved in volume to make room for noodles, dried fruits, cooking fuel and other essentials. It took two hours and various repacks to get it all in the boat but finally I squeezed myself and a 20 liter dry bag into the cockpit, snapped on the spray skirt and was ready to go.

plummeted into the mainstream and my first aid kit, clothes and other accessories were halved in volume to make room for noodles, dried fruits, cooking fuel and other essentials. It took two hours and various repacks to get it all in the boat but finally I squeezed myself and a 20 liter dry bag into the cockpit, snapped on the spray skirt and was ready to go.

At around 55 kilo's the heavily laden kayak sat low in the water making it hard to maneuver and portaging it if necessary would be difficult. I set off from the town of Nanqen in the late afternoon on June the 1st 2004. Around 15km south of town the water slowed almost to a standstill and continued at this pace for many kilometers. The Mekong in China does not stay still without reason. I guessed that it must have been backed up by either a unmarked dam or a huge avalanche creating a natural dam. Sure enough 12 kilometers down stream I heard a distant roar and finally eddied out above a massive class rapid. The river suddenly dropped on a tight right hand bend in a sheer sided canyon. Fortunately there was a disused horse trail cut into the wall with explosives on river right which allowed me to survey exactly what was creating the thunderous roar from dry land.

I trekked up part of the avalanche to the path to view a brutal class VI (Class VI tops the white water scale in terms of technical difficulty and danger) cascade created by a recent avalanche and extended for one kilometer around a sweeping left hand bend where the canyon widened into a more open valley. Dropping 12 meters in all, from one man eating hole (Extremely dangerous re-circulating hydraulic of water) to another before climaxing in an almost river wide ledge/ hole at the bottom, it was a monster and intimidating just to look at. The rapid was un-runnable and would become the first to be portaged as part of the Mekong First Descent. Although slightly disappointed that it would no longer be possible to kayak every inch of the Mekong, I was also relieved that there was a convenient path with which to bypass the rapid as anyone who entered it, regardless of their kayaking or rafting ability would be lucky to come out the other side alive.

I camped above the impressive drop and hoped I would not encounter such a monster in the much larger canyons down stream that would not have pathways around. This probably gave me a little too much time to think about what might be to come. In the back of every white water kayakers mind lurks a distant fear of some kind of white water disaster. For some it is being re-circulated into oblivion by a house sized hole, for others it's being pinned under water against boulders by the overwhelming force of the water. For me it is cruising down a sheer sided canyon towards a suicidal class six rapid with no way of stopping before going over the edge. With no locals around to find out the name of the cascade I called it "raging thunder" and although it proved easy to stop before this particular drop, the potential for disaster was clearly evident in the features it displayed. I also considered the consequences of the natural dam bursting under the strain of rising waters and releasing millions of tons of water suddenly into the gorges below. I moved on early the next morning and encountered a second rapid that the Japanese team had described as extremely difficult but at higher water it proved relatively predictable and I paddled it without scouting.

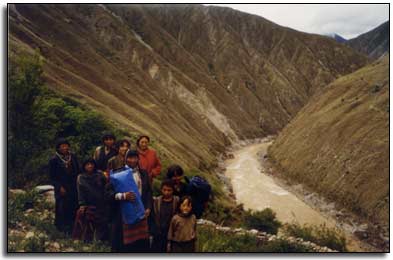

I crossed into the Tibetan autonomous region and into the area where the Japanese team had been attacked yet after meeting overwhelmingly friendly and hospitable locals until this point I found it difficult to  be too concerned. The setting was beautiful with robust stands of pine backed by snow covered peaks and waterfalls. Terraced fields of barley tended by farmers swayed in the swift breezes that wafted up the

gorges and Tibetans would yell out in amazement at seeing a foreigner in a weird looking boat cruising down rapids which I considered quite mild but they obviously perceived as life threatening. I had two encounters with deer, one of which was within 10 meters. I was finally in Kham Tibet and it was every bit as beautiful as I hoped it would be. I took many photos of the flora and landscapes I encountered. I camped on a sandy beach and noticed the next morning that the river had risen over 30 centimeters. I had to move fast.

be too concerned. The setting was beautiful with robust stands of pine backed by snow covered peaks and waterfalls. Terraced fields of barley tended by farmers swayed in the swift breezes that wafted up the

gorges and Tibetans would yell out in amazement at seeing a foreigner in a weird looking boat cruising down rapids which I considered quite mild but they obviously perceived as life threatening. I had two encounters with deer, one of which was within 10 meters. I was finally in Kham Tibet and it was every bit as beautiful as I hoped it would be. I took many photos of the flora and landscapes I encountered. I camped on a sandy beach and noticed the next morning that the river had risen over 30 centimeters. I had to move fast.

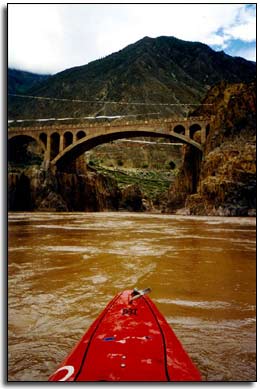

The next day as I approached Chamdo the landscape changed rather dramatically as the white water, which had been sporadic until then picked up several notches with dozens of class 3-4 rapids. The mountains became denuded of pine and major road construction was being undertaken by teams of hundreds of workers. Periodically explosions could be heard as obstructions were blasted from the canyon walls to widen tiny horse trails into what would soon become sealed expressways. Kham Tibet is changing. My passing would bring entire sections of roadwork to a standstill as hundreds of predominantly Chinese workers downed their tools to jeer as I bashed through standing waves and navigated around obstructions.

I encountered a huge sawmill just one kilometer north of town and the reason for the denuded mountains up river became evident. Thousands of logs lined the storage yard and work continued into the evening. The rapids continued straight through the heart of town. I must admit that I was struck by how entirely un-Tibetan the Chamdo looked. Until now the vast majority of the architecture encountered had been classical or rustic Tibetan in style yet Chamdo gleamed with aluminum, fresh paint and the feel of a new town. There were few buildings under 4 stories high and cement rather than rammed earth was the main building material.

As I passed the third and largest of the 4 bridges that span the Mekong in Chamdo, large neon lights flashed brightly on both sides advertising discotheques in new hotels. It looked as though the authorities had picked up a Hahn Chinese settlement from the coast and plonked it in Eastern Tibet. Although the sun was setting I decided to push on beyond Chamdo and ended up settling for a piece of riverbank flanked by a busy road.

After 3 days of paddling 10-12 hrs per day I had made very good time yet my body was starting to feel the strain. Nevertheless the rising river motivated an early start. I paddled along two sections with roads in the morning and at two separate points police cars followed my descent. I was concerned that they might stop me to cause problems with my permit (Something that had happened with the previous expedition to pass through this section) yet apparently they were just after some light entertainment as this crazy foreigner charged down various rapids. The first car even played some Shanghai rock over the loudspeakers as paddled a class 4 rapid, cool cops in one of the most restricted regions on earth is not what I initially expected!

The road abated around lunch time but horse trails continued to follow the river. Regular class III and IV rapids were encountered and by early evening I came across a short and steep class V drop that I identified as the twin falls rapid where the Pete Winn Expedition had called it quits only weeks earlier.  With trails and farmers homesteads nearby (Where horses could most likely be hired) it seemed an infinitely easier extraction point than where I was going. I estimated that if getting to a road from this location took his team one week to achieve then from the far more remote gorges down stream, if at all possible I would be looking at 3 weeks plus to make it back to civilization. With no villages at which to obtain food and no trails to follow, the only really viable way out of the pristine section would be by river and it was a wild guess as to just how dangerous the river would be. All I knew for sure is that the gradient drop would double in the downstream section ensuring increasingly difficult rapids and the gorges would become more precipitous. I could definitely see why the previous expedition pulled out at this point, the commitment level required to continue was at the top end of the scale and the stakes were high.

With trails and farmers homesteads nearby (Where horses could most likely be hired) it seemed an infinitely easier extraction point than where I was going. I estimated that if getting to a road from this location took his team one week to achieve then from the far more remote gorges down stream, if at all possible I would be looking at 3 weeks plus to make it back to civilization. With no villages at which to obtain food and no trails to follow, the only really viable way out of the pristine section would be by river and it was a wild guess as to just how dangerous the river would be. All I knew for sure is that the gradient drop would double in the downstream section ensuring increasingly difficult rapids and the gorges would become more precipitous. I could definitely see why the previous expedition pulled out at this point, the commitment level required to continue was at the top end of the scale and the stakes were high.

The following morning I ran the twin falls rapid through a large crashing wave formed in between the two large holes created by the falls. I called the rapid "Last Chance Cascade" (In the world of white water enthusiasts the first person to run a drop reserves the right to name it) as progressing much beyond this point requires that one commits to running the far more treacherous canyons that lie below.

About 30 kilometers down stream from last chance cascade the gorges began closing in and the rapids became longer, more violent and the gap between them decreased. I was delighted to see that the horse trail proceeded to follow the river throughout much of the day offering a lifeline back to civilization should I need it. Nevertheless it rose so high along the ridges that it would take a full day of dangerous climbing up one of the many avalanches to reach it and then more than a week from there.

Occasionally I would pass tiny green islands in the otherwise barren and eroding valley walls that revealed the presence of farmers. One has to see the incredibly tough environments in which these people can survive to appreciate just how resourceful they are. Entire families survive off as little as one acre of relatively flat land surrounded by otherwise precipitous cliffs, steep rills and avalanches.

I navigated 3 x class V and 14 x class IV rapids throughout the day; most were caused by the frequent avalanches that littered the valley. At several points I was forced to paddle around bends in sheer sided canyons with no idea what lay down stream or weather there would be a place to stop should I encounter a dangerous section. I continued until last light each evening and then hoped to find a farmers settlement low enough in the valley to trek to, besides that the alternative was sleeping under a sheet of wet plastic.

On the fourth evening around 8.30pm I rounded a bend to see a farmer's settlement that was only a 100m meter climb above the river. What appeared to be a 15 minute walk turned into a 90 minute saga as I made my way through a seemingly impenetrable maze of spiky shrubs and bushes. I was surprised to find it completely deserted and was forced to spend yet another night alone in the gorges yet it was a treat to have a fire and a dry abode.

The conditions were testing. Freezing winds whipped up the gorges every afternoon and caused my nose and

lips to blister and peel. My fingers began to crack at the tips from being wet for too many hours per day then drying out quickly in the evenings and by body ached in the night. When the winds were up it was often too cold to stop paddling and get out of the kayak, forcing me to spend up to 8 hrs at a time in the boat. The leg cramps and back pain were at times almost unbearable yet preferable to hypothermia. Its one thing to paddle in weather conditions that would regularly reach freezing but when you add constant splashes of water and 30 knot winds to the situation it might as well be minus 15 degrees.

lips to blister and peel. My fingers began to crack at the tips from being wet for too many hours per day then drying out quickly in the evenings and by body ached in the night. When the winds were up it was often too cold to stop paddling and get out of the kayak, forcing me to spend up to 8 hrs at a time in the boat. The leg cramps and back pain were at times almost unbearable yet preferable to hypothermia. Its one thing to paddle in weather conditions that would regularly reach freezing but when you add constant splashes of water and 30 knot winds to the situation it might as well be minus 15 degrees.

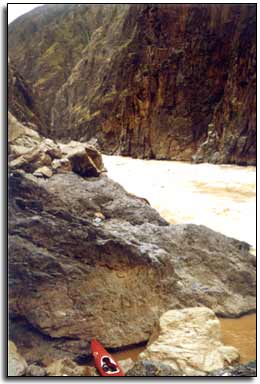

Going by map it appeared that I had successfully passed the steepest ravines. The map was wrong. The next morning I entered a long section of canyon that would not be traversable if necessary and did not see a single path or settlement all day. The rapids became more and more violent and at times were almost continuous.

If I swam I would have been lucky to get myself to the edge not to mention my kayak and the supplies that would be essential for getting out of the gorge. With evening temperatures dropping below freezing and without supplies one would be lucky to survive a week. The ravines were so steep that my GPS only worked occasionally and I doubted whether a chopper assisted rescue was possible in ravines that were many hundreds of meters deep and at times only 30 meters wide at the base, receiving unpredictable gale forced gusts of wind.

The rapids were testing the full limits of my kayaking ability and at several points I was forced to make risky runs above dangerous rapids not through choice but simply because there was no option to portage around the rapid and I was far beyond the point of turning back. On my map the gorge continued with the same features for another 150km.

I paddled kilometer after kilometer through gorges of white water but generally speaking it was possible to stop above the most difficult ones and scout a viable route down. At 2.00pm on day 6 it seemed that my worst kayaking nightmare would come true. I entered what looked like just another canyon but as I proceeded the canyon walls closed in until there were no avalanches or boulders to stop at. Only 18 meters wide the canyon had a steep gradient drop and powerful surges and boils pushed my kayak around like a cork.

Friction caused by the water along the canyon walls meant that the waterline along the edge was about a foot higher than in the middle where I struggled to maintain control in relentless whirlpools and surges. I was unable to stop and as I was forced down stream around the next bend I saw the horizon line drop away several meters and tufts of mist shot up into the air sporadically, a solid indication that there was a dangerous rapid below. I could not see a place to stop and my body surged with adrenalin. When I was within 30 meters of the drop I spotted several boulders on river right of the rapid. Behind one was a small eddy about one meter squared. I paddled for my life. The powerful boils attempted to push me away from the edge and every muscle was tweaked as I fought against the power of the water. As I neared the lip of the rapid a massive hole roared as it pumped mist into the air warning me not to miss the eddy.

Far below I could see that the rapid continued for at least another 200 meters before rounding a corner and had no idea what laid beyond although I could see what appeared to be the start of the next rapid. I strained and groaned, finally managing to pull into the tiny sanctuary behind the rock, it was a very close call and definitely scared the hell out of me but this was just the start. My body felt weak as the adrenalin subsided and I sat there for about 10 minutes to recuperate. A dangerous balancing act ensued as I struggled to get out of the kayak in an eddy that still surged with boils. I clambered onto a small cone-shaped rock while trying not to slip in nor let go of the kayak or paddle. Finally I managed to get secure footing and dragged up the boat, jamming it between the rock and the canyon wall.

I surveyed the class V+ rapid. There was no way of going back upstream or climbing out. I had to run the drop. At least I could now calculate the task before throwing myself into the violence. I worked out a route that entailed dropping off the rock into some fast flowing surges that came of the right wall, quickly skirting the powerful hole along the lower edge of the boulders I stood on and them cutting hard left above a second larger hole in the middle of the river. I would then have to use diagonal waves coming off the left wall to thrust me into a large hole/ wave that looked as though it could be bashed through with sufficient speed. From there a wave train continued to the bend and from there, I would just have to see what evolved. It was a very risky move. One error in the early stages could mean getting thoroughly munched by the intimidating holes and if lucky enough to survive them there was no way of getting to the edge before the next corner where I anticipated another drop would start.

It was a terrifying position to be in. I looked at the rapid for a long time before building up the courage to run it and under normal circumstances I would definitely choose not to attempt it but there were no other alternatives. It was not so much the dangerous drop that put the fear in me it was what lay downstream. Was this the start of a waterfall or long class 6 section?

I seal launched off the rock into the foray and the river quickly ushered me toward the first hole. Despite my best efforts the stern clipped the outer edge of the hole as I passed swinging my kayak down stream toward the next hole. Momentum was lost as I made a correcting stroke. Again I paddled with every ounce of energy my body could muster crossing the heart of the second hole before being slammed by its left edge and capsizing. A tense moment elapsed as I waited to feel whether the hole had me within its grips in which case I would most likely be recirculated repeatedly until out of my kayak and "if lucky" I would be released to swim down stream through the waves and whirlpools that would suck me under for periods of 5-10 seconds at a time to face the next violent rapid that lay below.

To my great relief the hole released me and I rolled up just long enough to take a breathe before being slammed heavily by the large whole wave on river left, hitting it side ways. Without sufficient momentum it re-circulated me violently twice before spitting me out into the wave train. I rolled up and tried to take a breath but received a lung full of water instead when a wave smashed over my bow.

I paddled as hard as I could to river right to see what lay around the corner before I was in it. The water in my lungs did not allow me to breathe properly and I became weaker with every stroke. The next thumping rapid began coming into view and again the mist shot above the horizon line. This time the avalanche that had caused the rapid was in clear view and I made for it yet most of the river was moving right to left forcing me back towards the center of the river. Before reaching the safety of the avalanche I was sucked into the next rapid. I straightened up to face my fate and spotted what may have been a "line" (safe pathway through the rapid) and committed instantly. I paddled straight over a huge rooster tail and skirted a house sized hole on the other side more by chance than anything else before entering a massive wave train followed by huge boils that sucked my entire boat under several times.

I could finally breathe properly again and re established control. The boils and swirls carried me to another powerful class V rapid but fortunately I could eddy out above this one and spent 30 minutes regaining strength before partially portaging it. I realized that a swim through any portion of this gorge would almost certainly have spelt death. On several occasions my kayak containing around the save volume of air as a 44 gallon drum was completely sucked under by the eddy lines and whirlpools forming in the middle of the river with only my head shoulders and paddle left above. A swimmer would be under for long periods and this was just on the relatively mild sections between vicious rapids.

The section had nearly brought me undone and for all I knew, far worse was probably just around the next bend, this played heavily on my mind as I lay resting cold and alone on the rocks. The level of physical and mental stress that I had just endured would not be sustainable for more than a day or two and I forced myself not to think about the fact that these conditions could quite possibly continue for over 150km. For the first time in my white water career I was genuinely scared and wished I could get the hell out of that gorge more than anything else on earth. I started to wonder if I would ever see loved ones again and actually tried to call my fiance by sat pm to let her know how much I loved her but there was no signal in this no mans land where it seemed almost a certainty that no human being had ever set foot. Looking down the sheer sided gorge to more rapids I felt an intense sensation of isolation and loneliness

Yet each time I pulled out of an eddy and into the main stream I had clarity of focus and determination that is hard to define. The second I felt the current grab the hull and move me down stream all sensations of fear and doubt disappeared completely. My entire mental and physical abilities became fixated on the sole goal of duplicating the exact movements I had created in my mind, the movements that would keep me on the narrow and constantly changing path to safety through ferocious and life threatening violence.

After more than 3 kilometers of continuous white water and 4 x class V + rapids that I would not normally choose to run the valleys broadened and eddies sent from heaven began to re appear. I was far from out of the Mekong Gorges but I was out of "Nightmare Canyon" and that night, despite being physically exhausted, I could hardly sleep. I was happy to be alive.

The rapids over the next 2 days were absolutely relentless. One, after the other, after the other. I lost count of how many rapids I scouted and ran, how many times I looked down stream and as a non religious person still found myself asking someone upstairs to make sure that the canyons I were entering would not contain un-portagable class VI rapids of continuous white water

I estimate that while in the Kham I made first descents down some 60 class IV rapids and 23 class V rapids. At relatively high water at least 12 of the rapids were "must run" rapids with no opportunity to portage around. I fully portaged two and a half drops and made "chicken runs" (Choosing an easier and safer run around the most dangerous section of rapid rather than the more obvious yet difficult route) down many of the more treacherous sections. I thought to myself how lucky the Peter Winn expedition was to have pulled out when they did. In the narrow canyons there was often no room for large rafts to stop before taking on extremely dangerous rapids and portaging would probably be necessary around at least 16 rapids taking many days. rafts are not suitable for the Mekong Gorges.

There was only on e rapid that I defined as truly un-run-able and named it "The three sisters" after the 3 consecutive river wide holes in which the river passed through, each of which was big enough top swallow a house not to mention a kayak or raft. It took 2 hours to portage around the 3 sisters on river left and I camped in a cozy little cave sheltered by oak trees just above the drops. Useful information for anyone crazy enough to go down that canyon again.

After 2 full days without seeing a single farmer's settlement or path I finally reached a group of mud walled huts on day 7. I was physically and mentally drained. Despite never seeing foreigners before the overwhelmingly friendly and curious Tibetans gave me 5 star treatment. The highlight of the stay besides the company was a delicious meal of Yak Yogurt with wild blueberries that managed to stain my hands for 2 days. Compared to Spam and 2 minute noodles it was a feast fit for kings.

I will never forget how kind and welcoming the Tibetan people are. We in the western world can learn a great deal from their respect and hospitality towards strangers. By day eight I was approaching the border of Yunnan and was becoming impatient to get there. About 15 kilometers north of the town of Yanjing the intense gradient droop of the river subsided and the rapids decreased in difficulty from predominantly class IV - V to class III - IV. I was hammering down and made good time. I was particularly keen to reach the Northern Yunnanese town of Foshan by nightfall to enjoy my first restaurant meal in 9 days and to meet my fiance who was flying into Zongdjian to meet me. I was tired and weary but pushed on.

My impatience almost cost me dearly. I passed the large silver signpost that marks the TAR border with Yunnan at 4.00pm and was determined to paddle on against a 30 knot head wind that whipped up spray from the surface of the river. Although the rapids in far northern Yunnan were relatively mild compared to the gorges of the TAR they were still potentially very dangerous. I ran various big water class IV rapids without scouting and each time I did bother to scout they just turned out to be relatively straight forward runs that I could have easily negotiated without scouting.

At 7.30pm I rounded a bend just 15km above Foshan to confront yet another class IV rapid. This one was slightly steeper than most. Without a clear view from the eddy of what lay below I should have scouted it but a mixture of fatigue, frustration at scouting so many previous rapids that turned out to be easy and impatience caused me to determine that it would most likely be another burley wave train. I peeled out of the eddy paddling hard to skirt a hole on river left and bashed through a large standing wave that I expected to be followed by a wave train. Upon breaking through the wave I was confronted by a huge hole about 8 meters wide and I was headed straight for the middle. There was no time to do anything accept power into it and hope to bash through. Bam! It felt like I hit a brick wall. I rose and was slammed down again, and again, and again I was being re-circulated by the hole.

I made the firm decision in the gorges not to bail out of my boat and swim until there was absolutely no other choice so I tried to sit it out and hoped that the hole would release me as they often do. It slammed me twice more before I felt a sort of release and saw daylight. Pheww!! I was relieved for about 1 split second until I realized that the roaring hole was still behind me. I was side surfing in front of it. Before I had time to establish control of the surf I was sucked back in.

One has to feel the force of a powerful hole to fully appreciate the violence involved. Anyone who surfs or plays in ocean surf has somewhat of an idea. Yet where as a surfer can relax in the fact that no matter how powerful a wave is the violence of being dumped will gradually subside, allowing the swimmer to establish control, river holes on the other hand continue with the same undiminished violent force for days and weeks.

I was running out of oxygen fast and realized that this beast of a hole was not going to release me as long as I was attached to the buoyancy of the kayak. It took a few seconds to separate from the boat because simultaneously doing back flips, summersaults and erratic acrobatic maneuvers while not breathing is particularly bad for ones orientation.

Once out I sank into the current and felt a flush of water push me out. I broke the surface and tried to take a breath and of course received a helpful breath of liquid. I was pissed. "Why the hell did you throw yourself in that after safely paddling hundreds of kilometers of significantly more difficult white water?" It's odd what goes through ones mind in such situations.

I only had a dry top and pants on instead of a full dry suit and could feel the freezing water seeping in. I tried repeatedly to take a breath but the water on my lungs prevented any air from entering. I looked back and saw the kayak and paddle some 20 meters upstream and began swimming for them. Without being able to breath I began to feel weak.

I looked down stream and saw another class IV rapid approaching. I tried to visually seek out a safe route through but with my line of site so close to the water all I could see were the tops of waves and foam. In the last moment I spotted a hole and swam left to avoid it. "I made it!!" then plopped straight into another even larger hole that tumbled me once and spat me out. I was really pissed when I realized I could still not take a proper breath with the water in my lungs. All I really wanted to do was swim upstream and drag the kayak to shore but I looked up stream and could no longer see it, then down stream to see yet another rapid approaching.

The lack of oxygen was making me weak fast. If I didn't get out of there immediately I would not have the strength to make the shore. I swam for it. I was amazed by how fast my energy diminished and each stroke seemed to add another 5 kilo weight to my arms. This was serious! I suddenly found my sub conscious reciting random white water statistics. "In 2003 long swims took more white water enthusiasts lives than blah" and I was so tired I honestly could have just given up there and then if I wasn't so pissed off. I'm not #! %*!#!! Going out like this I mentally yelled to the little demon on my shoulder that was persuading me to just relax and float through the next rapid. I dug deep, "GO, Go Go!!!" and made it to a boulder on river left clinging to it, too exhausted to stand up and walk to shore.

I have never been so beat in my life. I laid there in the freezing water for several minutes before noticing I was dizzy and shaking then started to worry that I might pass out in the water. I stood up and staggered on slippery river rocks to shore falling over twice. I could see some Tibetan houses just upstream and made for them. As I walked I could hear that my breaths were short and gasping and my lungs felt like they were getting burnt with each breath I was no longer shaking. I had hypothermia. I was so tired that for a moment I considered crawling into the space blanked I carried along with a sat pm and first aid kit in my PFD but sense got the better of me and I pushed on towards the mud walled homes.

I made my way up to a big old Tibetan house and knocked heavily at the door. No response. I wondered if I had the energy to make it to the next house when a sweet old Tibetan granny opened the door. As one would expect, she was a little shocked to see a swaying foreigner with hypothermia leaning against the door frame but within moments in true Tibetan style she had me warming by a fire sipping yak butter tea. It was the best cuppa I ever had. Dry clothes and blankets appeared, I was lucky to be so close to help. Such wonderful people.

I really did not expect to find my kayak and equipment again as the nature of such gorges is that there are few natural eddies and such for floating boats to get stuck in and the flow rate is at around 6 kilometers an hour so by the next day it could be anywhere within the next 100km and many stretches had no roads alongside. We had a replacement set of basically everything in case this happened but both my cameras were in the boat and I felt very disappointed to lose photos of such an incredible area that had never been visited by outsiders before.

I hailed a passing car the next day and headed for Zongdjian to meet up with our new director Brian Eustis and my fiance, Yutah. I anxiously scanned the river below at every opportunity as we drove along the bumpy dirt road yet it was only visible about 30% of the time and with each passing kilometer the chances of finding the boat diminished. More than 40 kilometers downstream from where I took the swim I spotted a tiny red dot on some rocks above a set of rapids some 200 meters below us. I stopped the car and to my utter delight identified the boat. A stiff 2 hr hike down and back up a steep avalanche ensued and with the assistance of a Tibetan passenger I retrieved the boat. I was surprised to see that nearly everything was still inside although totally waterlogged. Out of 5 rolls of film and 60 digital photos shot, only one roll of film was not destroyed by the water. Fortunately it contained several key land marks in the heart of the gorges so I could at least prove that I have paddled the section (There is no other way in or out to get photos) but it seems that the Mekong wanted to keep some of the most amazing sites in its most turbulent inner sanctums a secret from the outside world for a little while longer.

Navigating the Mekong gorges of the Kham has been without doubt one of the most challenging, dangerous and rewarding experiences of my life. I have never experienced another environment more hostile or unforgiving nor more magnificent and beautiful. One of the last great wilderness areas in China lies between Chamdo and Northern Yunnan and it has been my great privilege to be the first person to experience it. With expressways and sealed roads being cut along much of the Mekong's course north and south of this section, one hopes that the Authorities might see the value in leaving just a few islands of unhindered natural beauty to the earth and out of the relentlessly grinding wheels of "development'. Until now the extremely inaccessible nature of the gorges has provided effective protection against most human folly yet this could all change with just a few simple road network planning decisions. If there is one thing I learnt while traveling through Kham Tibet it is that there is no gorge or environment through which man cannot cut a road and his ambitions.

Dear Friends of the Mekong First Descent,

We are pleased to announce that the Team has successfully navigated the most logistically and technically challenging section of the Mekong River, "The Mekong Gorges of Tibet and Northern Yunnan". The section was not without its delays and dramas yet with perseverance and determination we managed to overcome all obstacles. Besides encountering permit problems and having most photos destroyed in a life threatening swim down long rapids, we have also had technical difficulties in downloading digital photos while in China due to the outdated software available here. Nevertheless we would like to get this latest update out to you all just to let you know that we are still on the move and on track.

We have been contacted by some of the largest magazines in the world to run stories on the expedition and TV news reports in 5 countries will soon be presenting news updates to their audiences. BBC radio has agreed to run updates on "Asia Today" and several publishing offers have been received for a book on the expedition which will further increase the exposure of the region.

Please be advised that we are now ready to enter phase two of the expedition through Thailand, Myanmar and Laos although we will intentionally keep media coverage a couple of weeks behind out progress so that we have time to get the products out. We apologize for not being able to get updates out to you all on the dates planned. Logistical difficulties have made it extremely difficult to get computer and Internet access.

Some hot gossip; To our surprise we managed to bump into another "Mekong First Descent Team" from New Zealand on the river just South of Jingong. Under a program supported by the new Zealand government they were attempting to trek, ride mountain bikes and paddle along the Mekong's entire route through all six countries yet only 300 kilometers into their trip they were forced to leave the Mekong Valley for hundreds of kilometers to travel down the Yangtze river valley in order to avoid the dangerous gorges mentioned in the attached dispatch. Unfortunately they were informed that there were roads through this area through which they could ride bikes. I can verify after paddling the gorges that this is definitely not the case. Therefore upon completion of their trip the "Kiwi" expedition cannot claim to have successfully completed a Mekong First Descent.

On the other hand the Mekong First Descent "Project" (Our expedition) has navigated the entire stretch and at no time diverted out of the valley or around the gorges so we can and intend to legitimately claim the title of the "Mekong First Descent".

Thank you all so much for your support of the project and stay online for more updates soon.

Best Regards,

Mick O'Shea.

Read About The Complete Mekong Descent

|